Córdoba has been awarded a World Heritage Site in three occasions by the UNESCO, and not only because of the Mezquita. Its rich heritage remains mostly unseen, it would be a tremendous effort to bring it all out to meet the eye. Not even ourselves, born and raised in this city, know half of what lies beyond many walls and doors. The monumental Plaza de la Compañía (the Square of the Society) is one of those cases. Despite its grand nature and its great location, right in the commercial sector of the city, it is barely visited by tourists due to the fact that its doors are firmly closed every weekend. What you see is what it will be for you.

Columns are not mere things standing straight. They are keystone to every building, they have always been valuable and demanded objects. History is full with testimonies that tell us how they were precious presents among kings, and ambassadors would carry them in their ships when sailing too far away lands as gifts.

There is very little industrial heritage in Córdoba for two reasons: Córdoba was never an industrial city, it never had much activity besides some agricultural factories. The second reason has to do with the location. The industrial areas needed to be close to city but could not be inside the city walls. Plus, since the winds in Córdoba blow generally from the West, to avoid fumes and pollution in the rest of the city, factories were placed only in the North and East (Ollerías Avenue and Ronda del Marrubial).Two chimneys are the Córdoba’s sole survivors, they outlived progress and city expansion throughout the XXth century. The most popular is known as the Chimeneón, or simply big Chimney, a vague memory of the olive oil industrial complex that Aceites Carbonell had next to the Malmuerta Tower.

Read more: Shot Tower: an unknown industrial remaining from the XIXth century.

This first edition of FLORA brought 8 international floral artists that transformed the Festival’s chosen patios into 8 unrecognizable stunning spaces. Located in some of the most representative buildings of Córdoba, this works have resulted in a delightful little tour through memory, art and heritage. These ephemeral floral installations will be open to the general public from the 20th to the 29th of October.

Now that we so desperately need to review and strengthen the idea of Spain, I search the words of the minds of our past, new old reasons that will help me understand this dreadful and immoral political context. It is a strange country, Spain.

This search took me through numerous authors, and I didn’t know what it was I was looking for until I run into one of Azorín’s books. Inside I found a beautiful description of Córdoba that soothed me. Azorin’s words build a clean and brief image of the city, a delicate, almost frail, touch containing the right amount of color and meaning. I walked the city inside my heart. It is a circle, every word is where it needs to be and not a comma is unneeded.

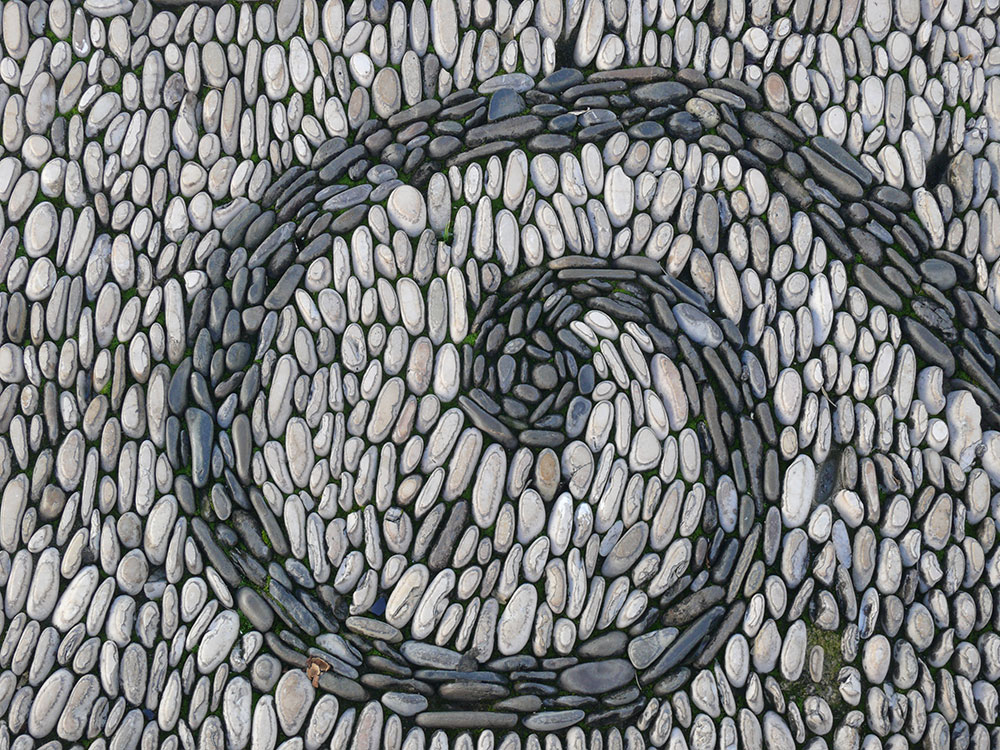

When promenading in Córdoba look not only what is in front of or above you. The floors are a distinguishing mark of the city. I am referring to the popular and historic pavement of its streets, squares and patios. There are three kinds of historical floors that have their root deep into Córdoba's beginnings.

Cordoba has more than 500 hectares of green zones and 82.000 trees distributed throughout the city. These astonishing figures come from the 44th National Conference of Public Parks and Gardens that is taking place these days in Córdoba. Within this vast number of trees there are unique ones in the city that, just like the Synagogue or La Mezquita, are worth a visit.

Walking is not only a kind recommendation but of the utmost necessity if you wish to truly know and enjoy Cordoba. Its tangled urban scene takes us again and again to the days of the Caliphate. We shall not see squared blocks nor parallel streets, instead an enormous and rich treasure lays at our feet waiting to be seen when passing by. The old city is big and round and this roundness happily result in walkable distances. Paseo is Cordóba's middle name.

It is around the middle of the XIXth century when marking the streets with personal names becomes a fashion. A questionable fashion that allowed Governments trends to do and undo almost at will since then. Before that, names were chosen by the actual users of those spaces. The names of streets and squares would traditionally tell us about their origin, purpose or common use; one could always relate to a story underneath.

Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy | Terms of Sale | Site map

Hotel 2** City | Registration No. H/CO/00731

© 2025 hotel viento 10

All rights reserved