Ronald Kitaj may not be as popular as his close friend David Hockney, and yet he is the one who introduced the School of London to the world by that same name. The school of London gathered pop British painters such as Allen Jones, Boshier, Caufield, Peter Phillips, etc.

The “errand Jew”, as he often spoke of himself, born in Ohio, although later would take on the British citizenship, first heard of Spain to his mother who befriended the brigadiers that fought in the Republican side during the Civil War. He visited Sant Feliu de Guíxols (Costa Brava) in 1957, it was then that his relationship with the Spanish culture begun and it would last 20 years.

Wikipedia states that Antoine Alexandre Henri Poinsinet was born in Fontainblue the 17th of November of 1735 and drowned in the Guadalquivir, in Córdoba, the 7th of June of 1769. The French playwright and librettist of the great Philidor –to whom Wikipedia dedicates more space trying to make sense of his odd character than to his work– would be the lead character in this curious story that happened very close to Hotel Viento10.

We dealt recently with Ronald Kitaj and his chiquita piconera, today we shall talk about another great British Pop character: David Hockney. He too made his peculiar grand tour around the romantic Andalucía. It was in spring of 2004 when he visited the three Andalusian architectural treasures: Córdoba, Granada and Seville.

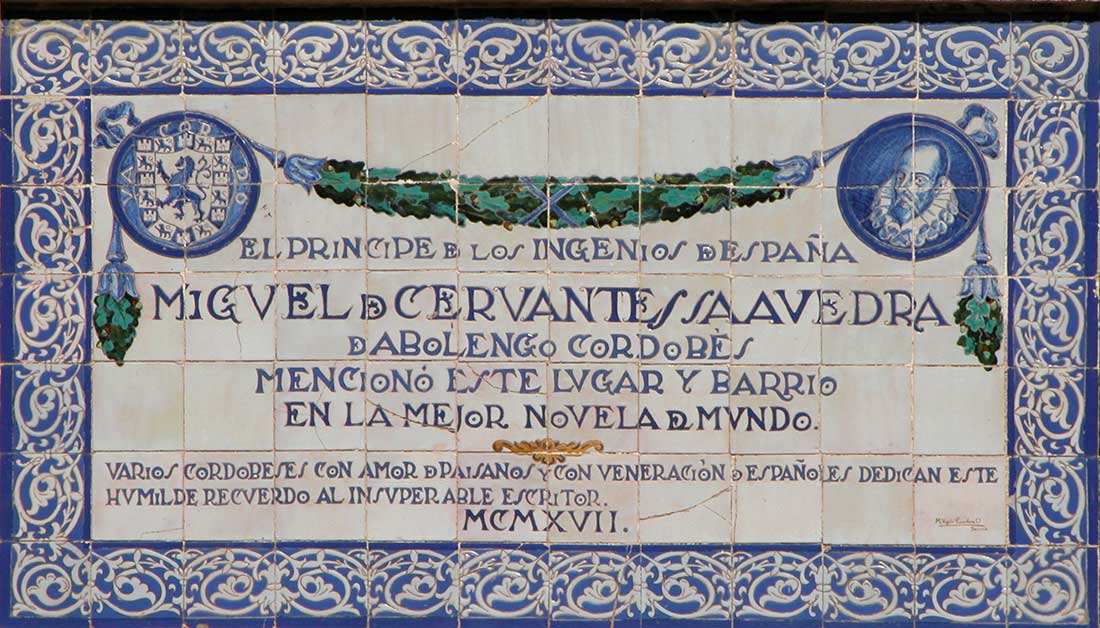

The biography of our most distinguished and universal writer, Miguel de Cervantes, gets eaten away by the mist of time. There are but a few true and verified facts about the life of the great author. Countless scholars and investigators have been trying desperately to disentangle the puzzled enigma of his life in order to build an honest portrait of Don Miguel. For instance, although it is not certain, many believe him to have been born in Córdoba.

José de la Vega, whose real name was Joseph Penso de la Vega Pasariño, was a Jewish merchant and writer. He was born in Espejo (Córdoba) around 1650, probably, into a Jewish family from Portugal or Galicia. One of many new Christians families that converted in Spain. He successfully engaged in trade and finances, though, he was also a fine author.

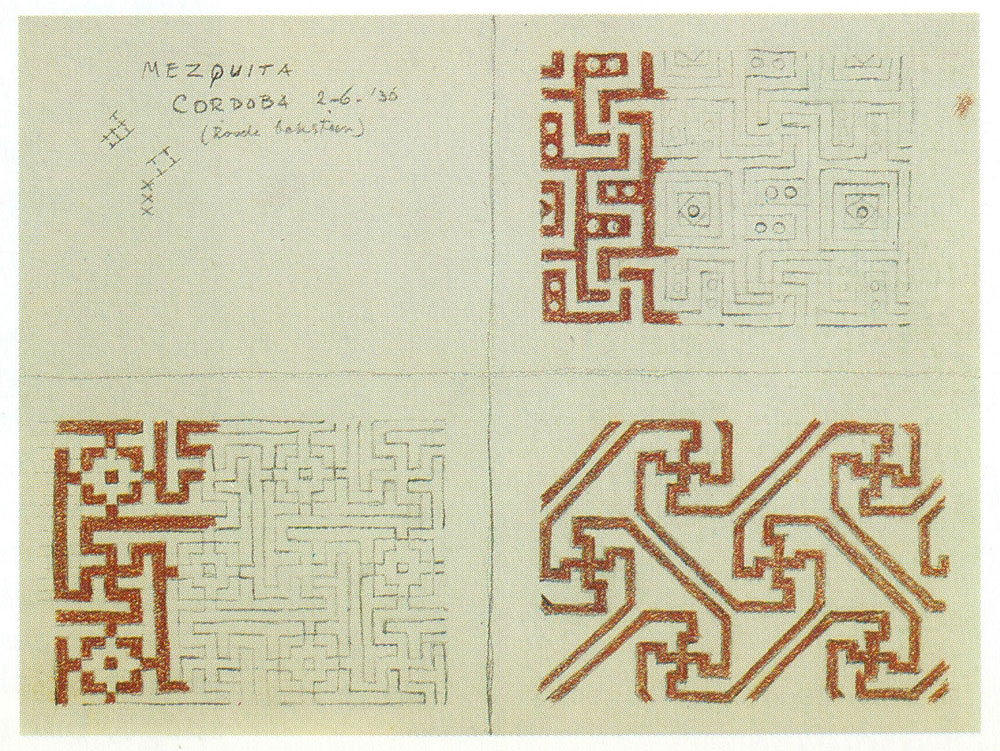

What is it that fascinate us so much about M.C. Escher? His impossible paintings and surreal mosaics seem to lack a expire date. There are a millions replicas of his drawings circulating the web, especially those reflecting his tours around Córdoba and Granada. Maurits Cornelis Escher, better known as M.C. Escher, traveled to Spain for the first time in 1926 and visited the Alhambra of Granada. He took many notes during his stay there and made sketches of its famous mosaics.

Despite the original building (1979) was to be located in the mountains near Córdoba (you can look it up above; the MOMA keeps the project plans safe), it was finally build 40 kilometers from Seville in 2004, in La Roda (between the regions of Burguillos, Guillen and El Ronquillo).

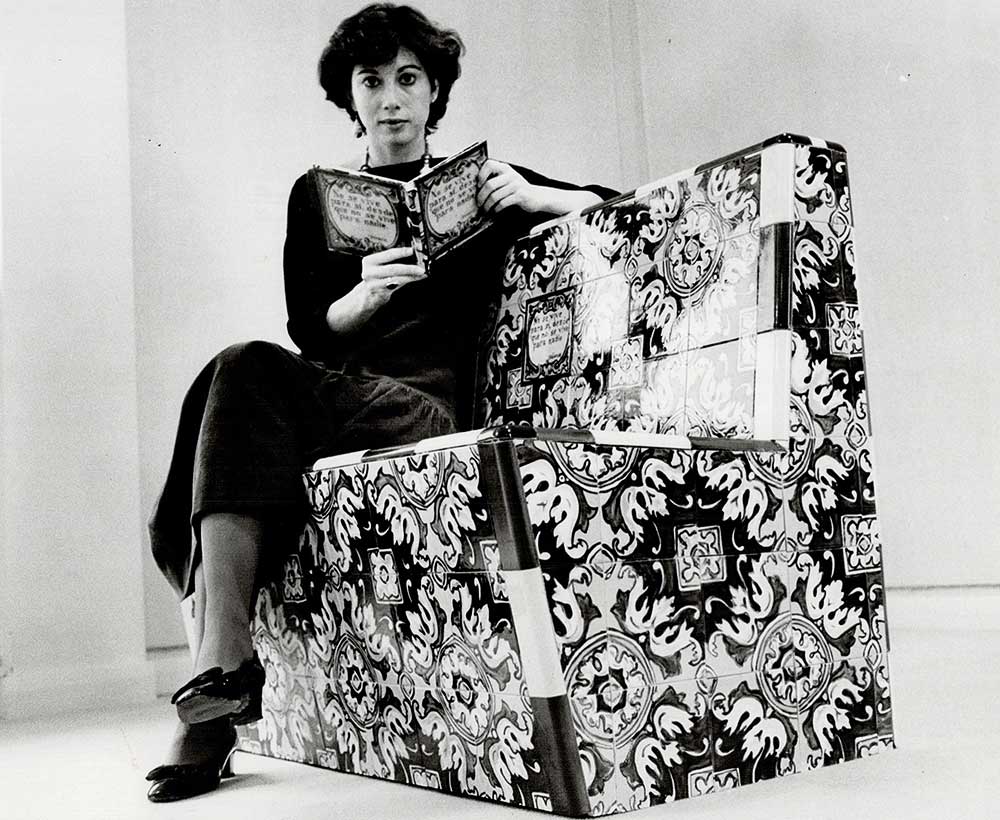

The circular bench made with the famous ceramic from Talavera that today slowly decays forgotten in the Agriculture Gardens (Los Patos), acted, back in 1925, as the limit enclosing the local Seneca public library. The library was but a small hexagonal hall containing little more than 2000 books that remained open until 1963. Then the library was demolished on account of prostitution being held in the premises at night. The circular bench is the only reminiscence of it, now rotting away because of idle institutions.

Read more: Jamelie Hassan’s artwork inspired on the tile bench in Córdoba.

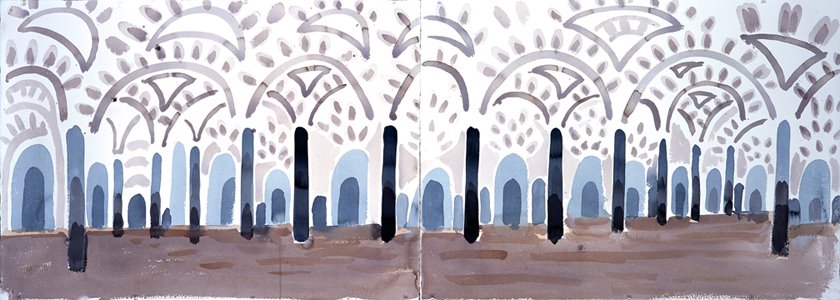

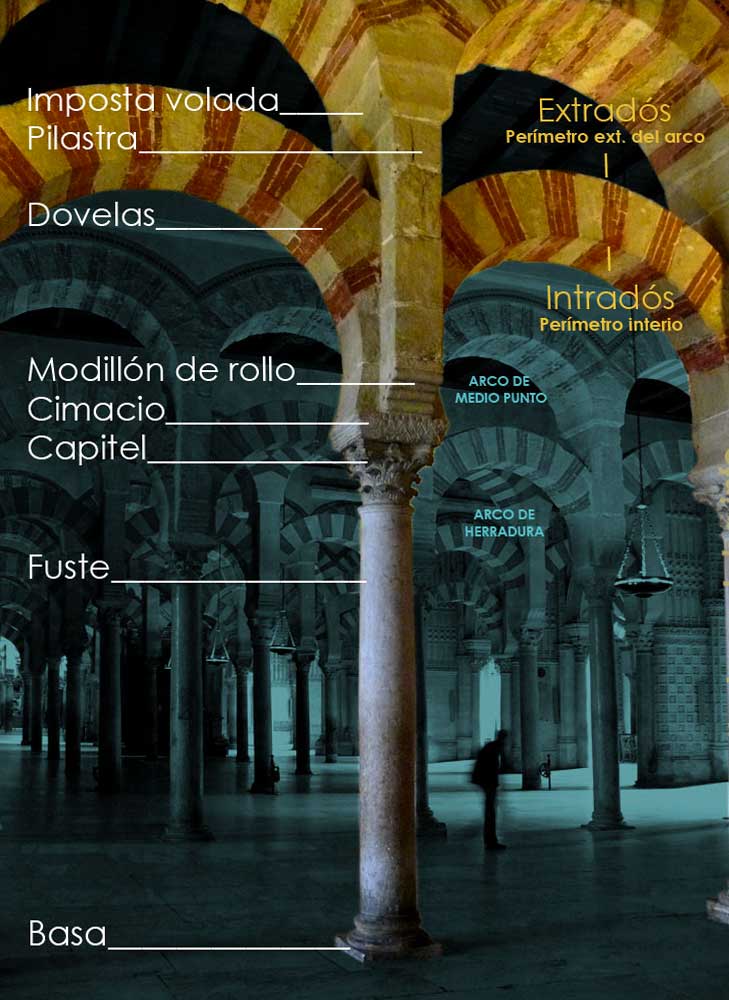

The Mezquita is the finest patrimony the city of Córdoba has. It is important for many reasons: it is the oldest building still in use in Spain; it shows the fusion of great civilizations that were able to cohabit in harmony at the time; it is a symbol to the Islamic world; and it also represents an architectonic reference that even nowadays leaves architects from all over the world in awe.

I am almost certain that at least one of you have heard of Gabi Delgado, well, that is if you are my age and have partied the night like my generation has. In my mind still echoes that little big pub in the old Jewish hood, “Varsovia” was the name back in the 80’s: cutting edge stuff.

Gabi Delgado was born in Córdoba in 1958, right in Manríquez street, or so the king said in a recent interview. He spent his childhood here but in 1966, he parted alongside his family to Germany (just like many other families did then). It is there, however, that his musical career starts; with time he would become one of the most influential musician in Germany.

Read more: The king of Deutsch Punk: a Córdoba man raised in Manríquez street.

The XVth century brought changes to Fine Arts and particularly to Painting. Gothic Art, its forms of representation (sculpture, glass and tesseras), was showing signs of depletion. That and the availability of new techniques such as oil painting or perspective were already giving notice that Painting will become the main form of representation up until the “recent” development of photography.

Under the category of “Iglesias Fernandinas” fall all the churches that Fernando III commanded to be built in Córdoba after the city was finally captured from the Muslims in 1236. The buildings are in-between Romanesque and Gothic architecture: a must for anyone that enjoys art and history. The churches are of a strong appearance, almost fortresses. Many are build in the same place of prior mosques using the same elements for the new construction.

Córdoba plays a powerful role in the world of Photography, having its highpoint during International Photography Biennial of Córdoba. This XVIth edition the Biennial will focus on war images. Between the 23rd of March and the 21st of May a wide range of activities will be taking place in Córdoba: workshops, documentaries of warlike conflicts, book presentations, conferences, round tables.

Read more: XVIth edition of the International Photography Biennial of Córdoba

When talking about ancient bells we ought to establish two different categories. The first category would apply to oldest bells in general, without taking into consideration their current use or disuse. The second category would account for oldest bells still ringing at the top of a bell tower nowadays. It is to this second category that the famous bell “Wamba”, from the Cathedral of Oviedo, belongs to. In fact, the bell preceded the bell tower: it was molten in 1219.

Because of the correspondence he had with his wife Clotilde when he travels, we know that Joaquín Sorolla visited Córdoba for the first time at the end of march in 1902. “Impressions are so fast and so many that my head feels like a madhouse. We treated ourselves to such an artistic binge in Córdoba” he writes in one of the letters.

Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy | Terms of Sale | Site map

Hotel 2** City | Registration No. H/CO/00731

© 2025 hotel viento 10

All rights reserved