We have already talked about Pedro de Córdoba and his panel the Annunciation, now exhibited in the Mezquita. In that same article Bartolomé Bermejo was briefly mentioned. He was a painter that worked mainly for the Crown of Aragón in Valencia and Zaragoza. Such was his talent that he even got to be of the main figure of the so called Catroccento in Aragon.

However, we scarcely know about the lives of these two talented painters from Córdoba as for centuries they were as good as forgotten. It is not up until very recently that their lives and work is being uncovered gradually and with great effort, almost as in an archaeological site. That had a lot to do with the development of museum studies during the XIXth and the XXth centuries. Then the archives and chambers were opened with a new light and curators and academics started to rescue many forgotten art pieces. The pioneer back then was Enrique Romero de Torres, who was the conservation specialist of the newly inaugurated Córdoba Museum. He would follow in Rafael Romero de Barros footsteps and study these two great figures. Gradually his work would draw the attention of other researchers and curators.

I took the liberty of copying an article published by Mr. Enrique in the official gazette of the Spanish Excursion Society in 1908. There, in the article, Enrique introduces the reader to his latest discoveries. To point out the vast difference between what we now know and what was then known, the painting of Santo Domingo was identified as one of Bermejo’s work in 1920, that is 12 years after this article was published. I copied the text exactly as it originally was written. I have merely attached the pertinent pictures for every painting cited by Mr. Enrique. It has not been an easy job but it was, without any doubt, worthwhile. Also, before you move on to the article, I would like to inform you about the exhibition on "Bartolomé Bermejo" that will take place from the 9th of October to the 27th of January of 2019 within the mighty walls of the Prado Museum. Surely it will be an unique opportunity that you must not miss for the world.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

The primitive men of Córdoba.

Pedro de Córdoba and Bartolomé Bermejo.

At the end of the XIIIth century Painting emancipated from servile imitation and infertile mosaics and adopted the Florentine style, the school of Giotto di Bondone. Which, without fully disengaging from the Christian Ideal, defended the importance of form regarding the contemplation of long forgotten Nature.

The new Art opened vast horizons and its principles were reproduced for over a century by Orgagna, Gaddi, Giottino, Spinelli, Juan de Melano and other famous disciples from the illustrious Giotto, even the pious Angellico. The new style reached new achievements that contributed to the greatness of the Faith but also respected the modesty of the Christian canon. However, then came the XVIth century and its profound reverence for the Classic world that would gradually make Art shift away from mysticism towards more voluptuous forms that threatened with relegating the religious tradition in favor of a sensual world.

The idealist Art permeated by an intense mysticism that colluded with form was able to create the works of Giunta de Pisa, Taffi, Cimabue and de Fiésole, the seraphic monk; and, in architecture, those wonderful monuments carved with the deepest faith typical of a Medieval Christian society were slowly and painfully fading away swept by the new revolutionary naturalistic painting techniques. This tenacious new spirit, despite the Christian crusade that for seven hundred years Spain fought against its neighbors of the Star and Crescent flag, managed to settle in and thrive although, for better or worse, it went hand in hand with the mysticism of the Church.

By the end of the XVth century a distinguished group of Spanish artists were painting using that same style, an intimate mixture between Christian mysticism and the austere demands of the Faith. To this particular group of artists belonged Pedro de Córdoba and Bartolomé Bermejo, and not only that, they were both key figures among those Primitive Men of Córdoba, those first men that, along with Sánchez Castro and Gonzalo Díaz, were the fathers of the Córdoba School. Unfortunately there is no biographical data about these great artists. Among academics, only Ponz, during one of his many trips, would mention the panel of the Annunciation by Pedro de Córdoba when visiting the Cathedral of Córdoba (the Mezquita), by then in an utter state of ruin. Cea Bermúdez would later add that note to his Dictionary. However, neither writer, nor even Pacheco and Palomino and others, managed to gather some information about the artist, and they knew nothing of Bartolomé Bermejo’s existence. And his life would remain forgotten until Piferrer in one of his works, Memories and beauties of Spain, in the year 1839, unveils that this great Córdoba artist was the name behind the famous panel La Piedad, which we can now contemplate in the Cathedral of Barcelona; as well as the stained glass of the baptismal chapel of that same temple.

Pedro de Córdoba, whose technique and style remembers Byzantine art, flourishes around 1475, he is an earlier artist than Bermejo, who made the panel of La Piedad around 1490; Pedro de Córdoba comes even before Alejo Fernández, an artist he could not imitate, as Mr José M. Tubino wrongly states in his book Murillo, because Alejo flourished from 1508 to 1525; so in any case the relationship could only have been the other way round.

The year of 1888, in the Ateneo of Córdoba, my defunct father, Mr. Rafael Romero Barros, read a brief Dissertation on the influence that Italian and the German schools had on the Spanish school of painting, and how that showed in the panel the Annunciation by Pedro de Córdoba. The Dissertation was initially published in the local newspaper but also in the official Gazette of the San Fernando Royal Academy of Arts. This essay presents us with a meticulous art critique of this artist’s best work; he points out the importance and the great influence that the panel had in other painters all around Spain back then; but it also discovered, among the vast work of Pedro de Córdoba, some portraits of Mr. Diego Sánchez de Castro.

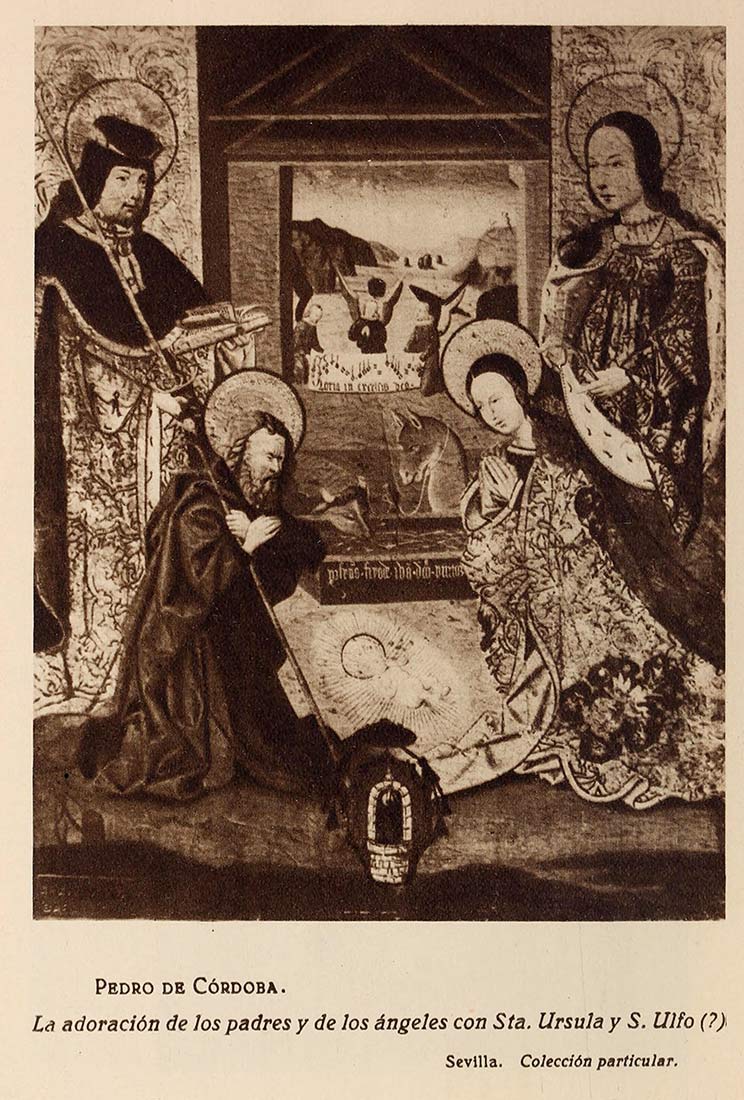

The Provincial Museum of Córdoba holds a beautiful panel that, without doubt, was part of an altarpiece by this artists. The panel shows a full-body Saint Nicolas de Bari dressed as pontiff holding a luxurious cane in his right hand and a opened codex in his left. His rich clothing are decorated with gemstones and fine brocades. In the private gallery of Mr. López Cepero’s heirs, in Seville, there is also an interesting painting, that goes by the theme: The adoration of the shepherds, signed: «Pedro, son of Iván de Córdoba.»

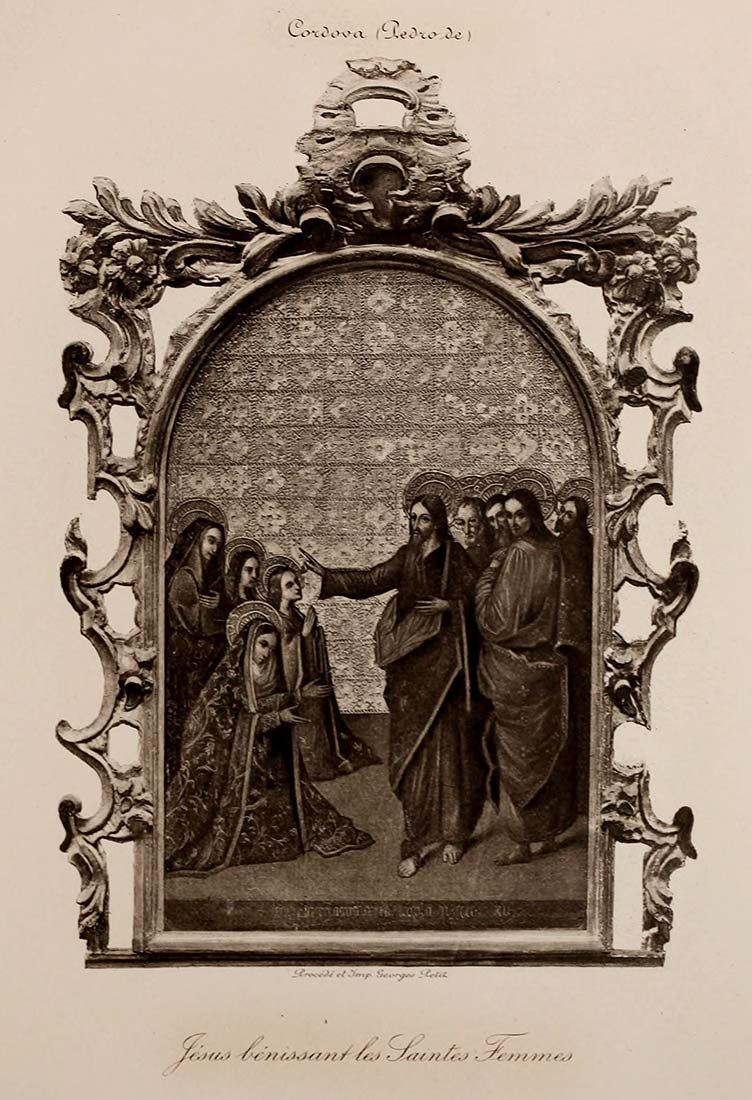

Also, we have seen published in the illustrious French magazine La Revu de l’Art another wonderful replica of this great painter: Cristo y las Marías (Christ and the Marys), from the Pacully collection, whose long shapes and proportions, along with the short legs, the gaunt yet expressive faces immediately make one think of el Greco, who probably used some of these artists for his own work.

Mr. Ramírez de Arellano, in his Dictionary of Córdoba artists, writes that there is a panel of Pedro de Córdoba in the Cathedral of Barcelona, although he has not seen it personally. I visited that same temple not two years ago and I did not see it, thus, I was unable to prove the presence of Córdoba artists in Catalonia at the end of the XVth century, as Sampere y Miquel states.

Pedro de Córdoba must have been a laborious artist, as Tubino is convinced that he was one of the pioneers of religious painting in Andalusia, and probably most of his work remains unknown and unsigned. It is a very common thing among painters before the XVth century not sign their work. Or worse it could have been sold to decorate foreign museums and galleries.

It should not surprise us, in these days of regeneration, that all our artistic heritage slowly disappears from the churches and cathedrals of Spain. And some times due to our ignorance, some times due to mere greed, we come in contact with our own past artists through foreign parties that celebrate our own heritage more so than we do. This is what happens with the work of Bartolomé Bermejo, whose work has recently been the center of a heated argument in French and English magazines. And it revolved around the San Miguel with the tamer, that belongs to the Vernher collection in London, and comes originally from Thous, a small village in Valencia.

This painting is signed by Bartolomeus Rubeus and came to be part of the Exposition of Primitive French artists that took place in Paris in 1905.

Could it be him, Bartolomé Bermejo, the author of the mentioned La Piedad that rests in the main hall of the Cathedral of Barcelona?

The distinguished writer Mr. Casellas stated that Rubeus is a Latin translation of the Spanish surname Bermejo, by doing so he made Herbert Cook along with L. Dimier retract themselves as to the origins of this great Córdoba painter. Also the professor Emile Bertaux was convinced Rubeus was originally from Spain and that he may be Bartolomé Bermejo himself.

Also, the famous magazine Cultura Española (Spanish Culture) published some quite pertinent comments, by Elías Tormo, on how the style and technique of the San Miguel did not match that of the La Piedad. Taking that into account, that could very well be the first painting style Bartolomé Bermejo used.

There is a recently published title by Mr. Sampere y Miquel, The Catalan Quattrocento, where the author writes about Bartolomé Bermejo making a meticulous study about his work in Spain and abroad, some examples are: La Piedad and the stained glass in the Cathedral of Barcelona; Santa Faz (Vick Episcopalian Museum); La Santa Faz (collection of Mr. Pablo Bosch, Madrid); La Santa Faz 2, Bermejo school (idem); Santa Engracia (collection of Mr. Gardiner, Boston E. V.); La Piedad, in Villeneuve-les-Avignon (Louvre-Paris); San Miguel (collection of Mr. Vernher, London); San Miguel (Avinyo Museum, France); The Annunciation (idem), and Ecce-Homo in Abysinia (collection of Mr. Ricardo Gimes, London).

Mr. Sampere y Miquel thought that the presence of Bartolomé Bermejo in Barcelona around 1490 was due to a high need of professionals and artists to build the Monastery of San Jerónimo, under the patronage of Pere de Tous the young. He thought this project caused the presence of a lot of Córdoba artists such as Jaime and Alfonso de Baena. As far as it goes we are certain that Bermejo was recommended by the monks from the Monastery of San Jerónimo in Córdoba to the monks in Catalonia to do what he had already done there. The fact that back then painters did not sign their work, plus the extreme likeness between these artists’ works, made it extremely difficult to know who did what, and this fact makes it difficult for us, people in the present, to truly appreciate those primitive original first painters. It is even quite frequent that these artists’ work are wrongly attributed to other painters.

That could be an explanation for the utter ignorance about the Bartolomé Bermejo.

Among the many paintings of the Provincial Córdoba Painting Museum, of which I am the director, I noticed that the most intelligent visitors usually stop by the same panel. It is a panel from the XVth century original from the Antón Cabrera Hospital. They are also captured by a painting from the XVIth century. The panel is three by two and half meters, divided into three parts. The central and biggest part shows the moment in which Christ is being whipped chained to the column by two executioners, and at the back of the panel we also see Saint Peter sitting before a fire while being inquired by two women. The other minor parts at each side are divided into four rectangles and depict, in an academic size, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Anthony of Padua, Saint Anthony the Great and Saint Francis of Assisi.

As far as I am concerned, I see many common features between the panel of The Annunciation in Barcelona and this whipping Christ in Córdoba.

Although it has been tried several times no photographic record has successfully been taken of this beautiful altarpiece, mainly due to the poor illumination conditions and the yellowish patina covering the painting. Therefore, only a representation can be attached here; a representation that was made with a lot of effort and dedication.

The second painting, which was also very difficult to portray, is a meter and fifty centimeters by two meters with the particularity of being an oil on canvas. It is also a representation of Christ chained to the column. Furthermore, when comparing both representations one realizes that they have an identical style and most likely were done by the same artist.

Were these paintings created by Bartolomé Bermejo? Could they have been painted after he came back from Barcelona?

We have always thought so, ever since we first exhibited them in the Museum, and then the famous French critic Emile Barteaux came to confirm it during a visit to this institution.

According to him, there is no doubt that the author of La Piedad of Barcelona must also have done the altarpiece of Córdoba.

Finally, I would like to thank the enthusiasm shown by the illustrious professor of the Central University, Mr. Elias Tormo, who, not long ago, encouraged me to write this modest article that you read today in this fine Magazine. I hope my efforts will help to unveil and uncover the truth about these great Córdoba artists: Pedro de Córdoba and Bartolomé Bermejo.

_____________________

Enrique Romero de Torres.

Córdoba, September of 1907.

The official gazette of the Spanish Excursion Society. 1908.