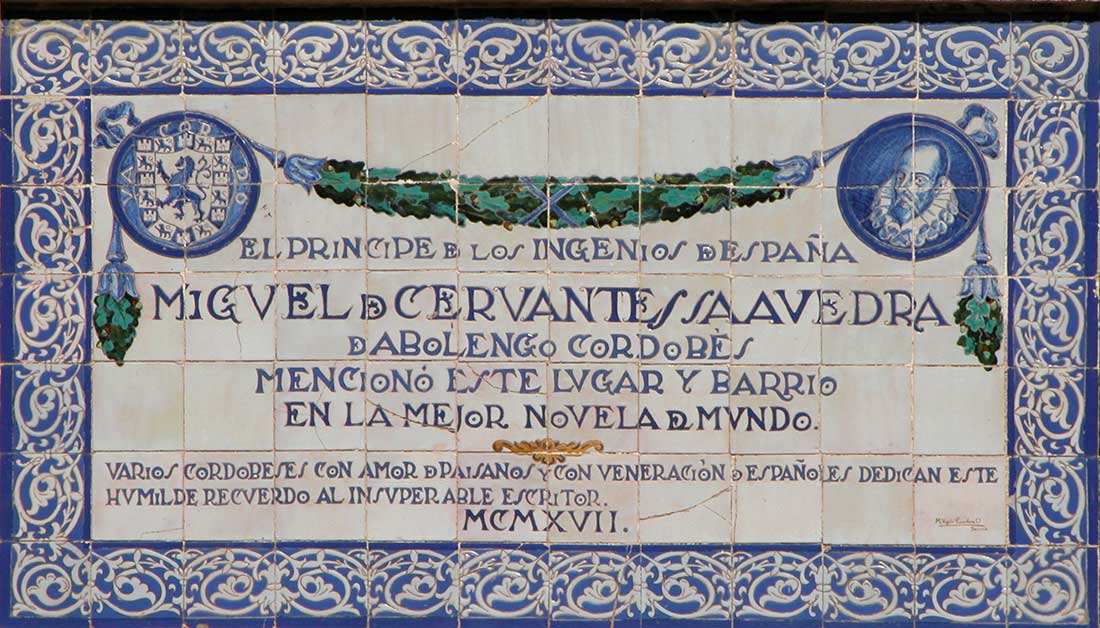

Having born in Córdoba or not, what we do know is that the city and, especially, the “Plaza del Potro” (the “Colt Square”) are essential settings in both Cervantes and Don Quixote's lives.

We know for a fact that his grandparents, on his father's side, were from Córdoba.

We also know for a fact that his father, Rodrigo de Cervantes y Torreblanca, was born in Córdoba and that surgeon was his profession.

And we also know that Rodrigo and Leonor, his wife, moved to Valladolid from Alacalá de Henares (where Cervantes himself was supposedly born) in 1552, in order to keep practicing as a surgeon without qualification. Despite his efforts, he was finally imprisoned and his assets seized because of that. After having proved his cleanliness of blood and status they returned to Córdoba, Miguel de Cervantes was then 5 years old. They lived in a little property in Gragea street, right behind the Plaza del Potro, and very close from Viento10, until 1563.

That is to say that Cervantes enjoyed his childhood in the busy Plaza del Potro, a hive of activity, horse trade most of all. At the direct wishes of Felipe II the royal stables of Córdoba were in charge of breeding the Spanish horse. The best horses were bought in Córdoba at that time.

Cervantes used many of his early memories of this popular square to build some of the landscapes of his masterpiece.

Part 1. CHAPTER III

WHEREIN IS RELATED THE DROLL WAY IN WHICH DON QUIXOTE HAD HIMSELF DUBBED A KNIGHT

“The landlord, who, as has been mentioned, was something of a wag, and had already some suspicion of his guest’s want of wits, was quite convinced of it on hearing talk of this kind from him, and to make sport for the night he determined to fall in with his humor. So he told him he was quite right in pursuing the object he had in view, and that such a motive was natural and becoming in cavaliers as distinguished as he seemed and his gallant bearing showed him to be; and that he himself in his younger days had followed the same honorable calling, roaming in quest of adventures in various parts of the world, among others the Curinggrounds of Malaga, the Isles of Riaran, the Precinct of Seville, the Little Market of Segovia, the Olivera of Valencia, the Rondilla of Granada, the Strand of San Lucar, the Colt of Cordova, the Taverns of Toledo, and divers other quarters, where he had proved the nimbleness of his feet and the lightness of his fingers, doing many wrongs, cheating many widows, ruining maids and swindling minors, and, in short, bringing himself under the notice of almost every tribunal and court of justice in Spain; until at last he had retired to this castle of his;(...)”

Part 1. CHAPTER XVII

IN WHICH ARE CONTAINED THE INNUMERABLE TROUBLES WHICH THE BRAVE DON QUIXOTE AND HIS GOOD SQUIRE SANCHO PANZA ENDURED IN THE INN, WHICH TO HIS MISFORTUNE HE TOOK TO BE A CASTLE.

“The ill-luck of the unfortunate Sancho so ordered it that among the company in the inn there were four woolcarders from Segovia, three needle-makers from the Colt of Cordova, and two lodgers from the Fair of Seville, lively fellows, tender-hearted, fond of a joke, and playful, who, almost as if instigated and moved by a common impulse, made up to Sancho and dismounted him from his ass, while one of them went in for the blanket of the host’s bed; but on flinging him into it they looked up, and seeing that the ceiling was somewhat lower what they required for their work, they decided upon going out into the yard, which was bounded by the sky, and there, putting Sancho in the middle of the blanket, they began to raise him high, making sport with him as they would with a dog at Shrovetide.”

And finally, there is what we would nowadays call a short story. A brief tale that precedes the second part of Don Quixote's adventures, and which is also the origin of the famous Spanish saying: “¿son galgos o podencos?”. The saying advises us not to get carried away by trifles when the big menace is at hand.

THE AUTHOR’S PREFACE

“In Cordova there was another madman, whose way it was to carry a piece of marble slab or a stone, not of the lightest, on his head, and when he came upon any unwary dog he used to draw close to him and let the weight fall right on top of him; on which the dog in a rage, barking and howling, would run three streets without stopping. It so happened, however, that one of the dogs he discharged his load upon was a cap-maker’s dog, of which his master was very fond. The stone came down hitting it on the head, the dog raised a yell at the blow, the master saw the affair and was wroth, and snatching up a measuring-yard rushed out at the madman and did not leave a sound bone in his body, and at every stroke he gave him he said, “You dog, you thief! my lurcher! Don’t you see, you brute, that my dog is a lurcher?” and so, repeating the word “lurcher” again and again, he sent the madman away beaten to a jelly. The madman took the lesson to heart, and vanished, and for more than a month never once showed himself in public; but after that he came out again with his old trick and a heavier load than ever. He came up to where there was a dog, and examining it very carefully without venturing to let the stone fall, he said: “This is a lurcher; ware!” In short, all the dogs he came across, be they mastiffs or terriers, he said were lurchers; and he discharged no more stones.”

perfect stay in cordoba. Beautiful quite place in centre of Cordoba with very gentle, even "zen" owner. Design hotel room Excellent "fresh" breakfast Private parking space nearby. All you need for a beautiful stay in Cordoba!

perfect stay in cordoba. Beautiful quite place in centre of Cordoba with very gentle, even "zen" owner. Design hotel room Excellent "fresh" breakfast Private parking space nearby. All you need for a beautiful stay in Cordoba!

Luxurious hospitality. When we got to Córdoba it was 108ºF and we could not be more miserable. Then we walked into Viento 10 and Gerrardo, the owner, greeted us with refreshing lemonade and a friendly conversation, exactly what we needed. The rest followed suit, with his recommendations for restaurants and the beautiful room and amenities, which included access to a spa.........

Luxurious hospitality. When we got to Córdoba it was 108ºF and we could not be more miserable. Then we walked into Viento 10 and Gerrardo, the owner, greeted us with refreshing lemonade and a friendly conversation, exactly what we needed. The rest followed suit, with his recommendations for restaurants and the beautiful room and amenities, which included access to a spa.........

Cordoba merece un hotel como este. Maravilloso trabajo de rehabilitación para conseguir un espacio único y muy agradable...acogedor...bien climatizado y con espacios higiénicos muy modernos y cómodos. ...buena ubicación y un trato muy simpatico

Cordoba merece un hotel como este. Maravilloso trabajo de rehabilitación para conseguir un espacio único y muy agradable...acogedor...bien climatizado y con espacios higiénicos muy modernos y cómodos. ...buena ubicación y un trato muy simpatico

kleines, tolles hotel. Ganz persönlich geführtes Hotel, in einem historischen Gebäude modern interpretiert. Sehr geschmackvoll, sauber und ruhig. Zu erwähnen ist das gesamte Personal, welches bei Empfehlungen für Restaurants und anderen Fragen immer tolle Tipps gegeben haben. Die Zimmer sind sehr unterschiedlich. Wir hatten ein sehr kleines, kuscheliges Zimmer im 1. Stock. Für drei Nächte völlig ausreichend. Bei Temperaturen um 40 Grad haben wir die kleine Dach-Terrasse leider nicht genießen können, sonst ein toller Ort, um mal zu relaxen. Alles in allem ein schöner Aufenthalt. Danke an Carmen , Gerardo und sein Team!

kleines, tolles hotel. Ganz persönlich geführtes Hotel, in einem historischen Gebäude modern interpretiert. Sehr geschmackvoll, sauber und ruhig. Zu erwähnen ist das gesamte Personal, welches bei Empfehlungen für Restaurants und anderen Fragen immer tolle Tipps gegeben haben. Die Zimmer sind sehr unterschiedlich. Wir hatten ein sehr kleines, kuscheliges Zimmer im 1. Stock. Für drei Nächte völlig ausreichend. Bei Temperaturen um 40 Grad haben wir die kleine Dach-Terrasse leider nicht genießen können, sonst ein toller Ort, um mal zu relaxen. Alles in allem ein schöner Aufenthalt. Danke an Carmen , Gerardo und sein Team!